If I were to describe the persistently foggy energy that has shrouded our lives since the coronavirus pandemic, which seems so difficult to shake off, I would call it an air of inner displacement. We all lost something – perhaps an ease, a certainty with which we moved through the world.

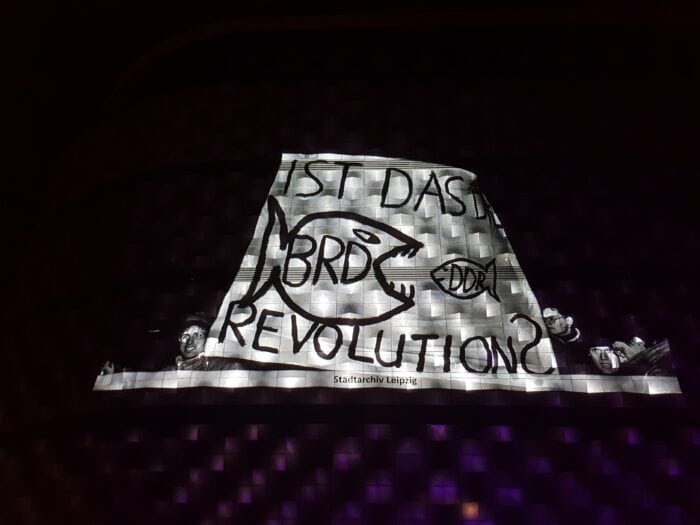

While this particular calamity was universal, this loss of innocence was not; for many peoples to be displaced by History with a capital H is just another Tuesday. I was duly reminded of this during this year’s DOK Leipzig – International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film. Arriving at the Leipzig train station from Berlin on what turned out to be a very rainy Monday, the appropriate ambiance was set to soak in the festival programme.

DOK Leipzig is the oldest documentary festival in the world – started in 1955 in then East Germany, it was its first independent film festival. Since its genesis, the festival has added a robust animation and industry sections and was attended by 42 000 visitors this autumn. Sweden was represented by Maria Fredriksson’s The Gullspång Miracle, a peculiar case study of familial displacement. Indeed, in this 66th edition, the theme of displacement was running through each film I had the pleasure to watch.

The festival’s focus on Central and Eastern Europe in the Panorama section this year was particularly relevant in this regard. I welcomed it since, in my opinion, no European peoples know the throes of History and its toll on individuals and societies better than us – a bitter boast. I’m from Lithuania, and it’s all too familiar to me how the lingering effects of the violence of the Soviet Empire continues to shape our collective psyche.

The world premiere of Who, If Not Us? The Fight for Democracy in Belarus by Juliane Tutein, for whom this was a feature debut, was, however, a reminder that to be in a process of recovering from collective trauma is, nevertheless, to be in a place of privilege. Tutein focuses on three Belarusian activists, all women but from different generations, following the brutal crackdown of the 2020 mass protests – assisted by Russia, eager to exert its influence. Thousands of dissidents were arrested, tortured and now face decades of imprisonment. The perseverance of these activists, mostly in asylum, is sobering. For one protagonist, Tanya, one type of displacement intertwines with another, as she flees to Ukraine after Russia’s renewed invasion to reunite with her family – an ironic kind of shelter from Lukashenko’s regime. While Tanya, like many other Belarusian activists, shifted focus to aiding Ukraine, their fighting spirit leaves no room for malaise, and I wasn’t the only one tearing up in the audience when the credits rolled. During the Q&A, Darya, the youngest activist, presented the Solidarity Postcards Atelier campaign and the audience had a chance to write letters to political prisoners inside Belarus. In the festival’s industry section, the Belarusian Independent Film Academy, a dissident organisation, gave a talk about the urgent need to support independent cinema in Belarus.

Not all shelter sought within Eastern Europe is because of autocracy, of course. Beauty and the Lawyer, a feature debut by Hovhannes Ishkhanyan that received the Silver Dove (award for the best documentary for an up-and-coming director), also spoke of perseverance against all odds. Garik and Hasmik set out to raise a family their way despite the vitriol that Garik’s queerness receives in Armenia. While he performs in drag, discusses sex work, and builds a house, heavily pregnant Hasmik fights for queer rights in the judiciary. While the audience, including myself, were very enthusiastic, the cast and crew were sombre. The Q&A was shadowed by the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh, with its entire Armenian population forcibly displaced the month prior. Hasmik reflected on her family’s social abjection: “We had it easy.” To them, their struggles now seemed infantile as a humanitarian crisis enfolds and the threats coming from Azerbaijan grow louder and louder. Still, even with Armenians once again under an existential threat, the family’s determination to live authentically and build their utopian family at home instead of migrating, is praiseworthy.

Queer Eastern Europeans often feel an inner displacement due to conservative anti-queer propaganda that proclaims we’re not an indigenous part of our region but an ideological import. Kristina, by Nikola Spasić, was one of my personal highlights, a Serbian portrait of an unlikely hermit who is building her utopia at home. Kristina’s days consist of hunts for antique furniture, sex work, intricate flower arrangements and religious devoutness – she has long transitioned and now basks in the aesthetic realm previously reserved for the cis bourgeois. Fact and fiction blend seamlessly into a depiction of elegant valour.

Personal resistance is no better conveyed than in Deliverance, a Brazilian short from Joana Claude, which shows her reckoning with a sexual assault she survived years ago. In one take, Claude destroys the object that brought about her trauma — a wardrobe delivered to her parents’ home. I could feel the collective catharsis sweep over the audience as we watched her rip apart the long hated object and set fire to it. I recognised a great yearning for this type of cinema that offers communal healing – a powerful exorcism of violent memories, a spiritual retribution.

Healing after collective trauma is not a straightforward process. Two films were screened that grappled with this issue differently. The first, Kumva – Which Comes From Silence (by Sarah Mallégol, whose French parents lived in Rwanda before the genocide), foregrounds dialogue. Tutsi mothers give testimonies to their children of their survival and their fathers’ deaths; those same children reminisce between themselves and later converse with Hutu whose fathers were the perpetrators. It’s a stoic approach, all Rwandans actively labouring to wrestle their country out of a shellshock. The second film, Disturbed Earth, is, on the other hand, a silent meditation on the Srebrenica massacre by Kumjana Novakova and Guillermo Carreras-Candi. Interspersed with poetic intertitles that wrestle with the impossibility of language to contain horror of genocide, the film follows daily routines of three ageing survivors who continue to live beside the site where their families and relatives were murdered in 1995. Only they really live beside life itself, in self-sustaining solitude, life seemingly devoid of the most basic societal support. Healing remains a question.

Another pair of documentaries with parallel themes grappled with the bittersweet consequences of overcoming geographical displacement only to find that ‘home’ does not become any less elusive. Self-Portrait Along the Borderline by Anna Dziapshipa is an intricate exploration of her heritage in the rubble of the Abkhaz–Georgian conflict. Being of both ethnicities, Dziapshipa hasn’t seen her Abkhaz part of the family since the ethnic conflict exploded in 1991. A separatist republic shouldered by Russia, Abkhazia was the crown jewel of the Soviet Empire and a major tourist destination, now nearly impossible to enter through the titular border with Georgia. Reflecting on her troubled childhood in Tbilisi and her Abkhaz grandfather’s life, Dziapshipa weaves archival footage into a playful collage of personal identity and 20th century Georgian history. Once she manages to cross into Abkhazia, which she hasn’t visited since childhood, all romantic notions fall apart. Both Abkhaz architecture, formerly splendid, and her family home are totally derelict – aren’t these ghostly buildings displaced, too? The search for home provides no more than a failed reconciliation.

Homecoming is tightly tied to displacement, but so is homemaking. The most atmospheric film I’ve seen in DOK Leipzig, Waking up in silence by Mila Zhluktenko and Daniel Asadi Faezi, is a seemingly idyllic exploration of summer quietude. The camera follows children playing outside during Summer holidays, bringing up a familiar, nostalgic feeling; only soon it dawns on me they’re not on a holiday and their childhood is nothing like my own. Currently residing in former military barracks, Ukrainian children practise German in sunlit playgrounds and scribble anti-Putin slogans on the pavements. Although their days are filled with tactile adventures, a sort of calm permeates the film that signals that, nevertheless, even if the children seem to feel at home, everything remains on pause, their childhoods muted.

My personal favourite, 30 Kilometres per Second by Jani Peltonen, who received the Silver Dove Short Film award, was about a very unusual type of displacement. The narrator struggles with proprioception – an awareness of her body’s occupation and movement in space; her own senses are quite literally misplaced. She reflects on the 1960s in Finnish TV history with highlights of, among others, American celebrity craze and a ban on dancing dating from the Middle Ages that was still, somehow, in effect. Finland itself was peculiarly placed in-between the Cold War blocs and its cultures, and so the archival footage is fascinating. Editing rhythmic and narration hypnotic, it is entirely possible to lose one’s own proprioception while watching this short film. I myself felt transported to a very mysterious time and place.

Another favourite was also magnificently playful, dug into the 1960s history and reflected on the ambiguity of some places that are in-between different worlds, both geographical and metaphysical. Bo Wang’s An Asian Ghost Story received the Golden Dove Short Film award. Narrated by a ghost who is trapped in a wig of real human hair, it is an exquisite essay on Hong Kong’s similarly extraordinary position in the region as a transport hub, on the permanence of the human soul, and on the historical “communist hair” ban (you read that right) which is somehow less bizarre than the historical “Asian real hair” buying craze in the USA in the ‘60s that resulted in the ban of Chinese wig imports. The documentary was a masterclass in blending fantasy and fact, and I enjoyed every moment of it.

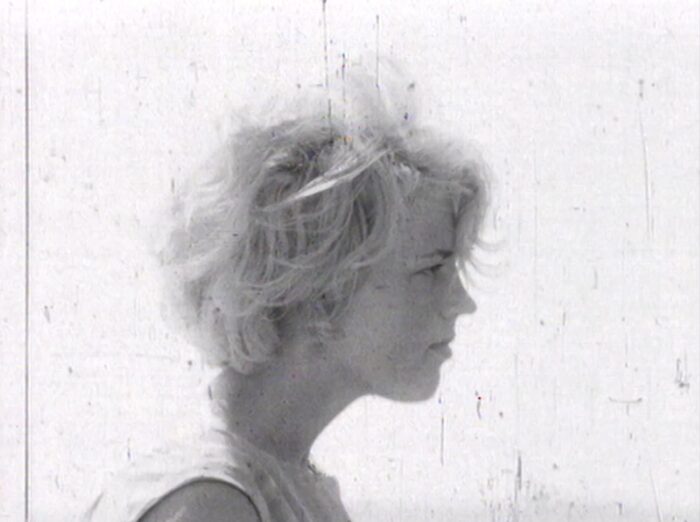

On a gloomier note, there is always the ultimate liminal space on Earth – Chernobyl. In this case, displacement from home should, in fact, be permanent, only that most people are trapped by poverty and so continue to live in the surrounding contaminated areas. In an illuminating duology by Maja Weiss called Boy, Bloodbrother of Death from 1992 and 2012, I followed Anatoli’s life as he grew from a heartbreakingly poor and kindhearted child into a man with no prospects for work or a better life, still living with his mother and brothers, all trapped by ongoing social issues and unable to leave the forsaken ground. Social wilting stifles the air as much as radiation. Anatoli is currently fighting, the filmmaker noted during the Q&A, and they plan to make another film together in ten years’ time. Who knows where we’ll see Anatoli next, but I have a suspicion that such kind of social displacement is as permanent as radioactive contamination.

It might seem banal to talk of the human condition, but I think it is, at its core, no more than persistence despite displacement. We persist in our search for home, for safety, for freedom, even if we don’t leave home, even if we turn out to be looking for an illusion. Despite evidence to the contrary, I left Leipzig with a firm faith in this search. The chorus of voices I had the privilege to witness reminded me of something I had been dulled into forgetting in recent years. It’s a discovery that the documentary genre excels at – the world is not only on fire; it’s also a much more interesting place than I tend to think.

The Swedish translation of the report was made by Olga Ruin and published in FLM Nr 65.